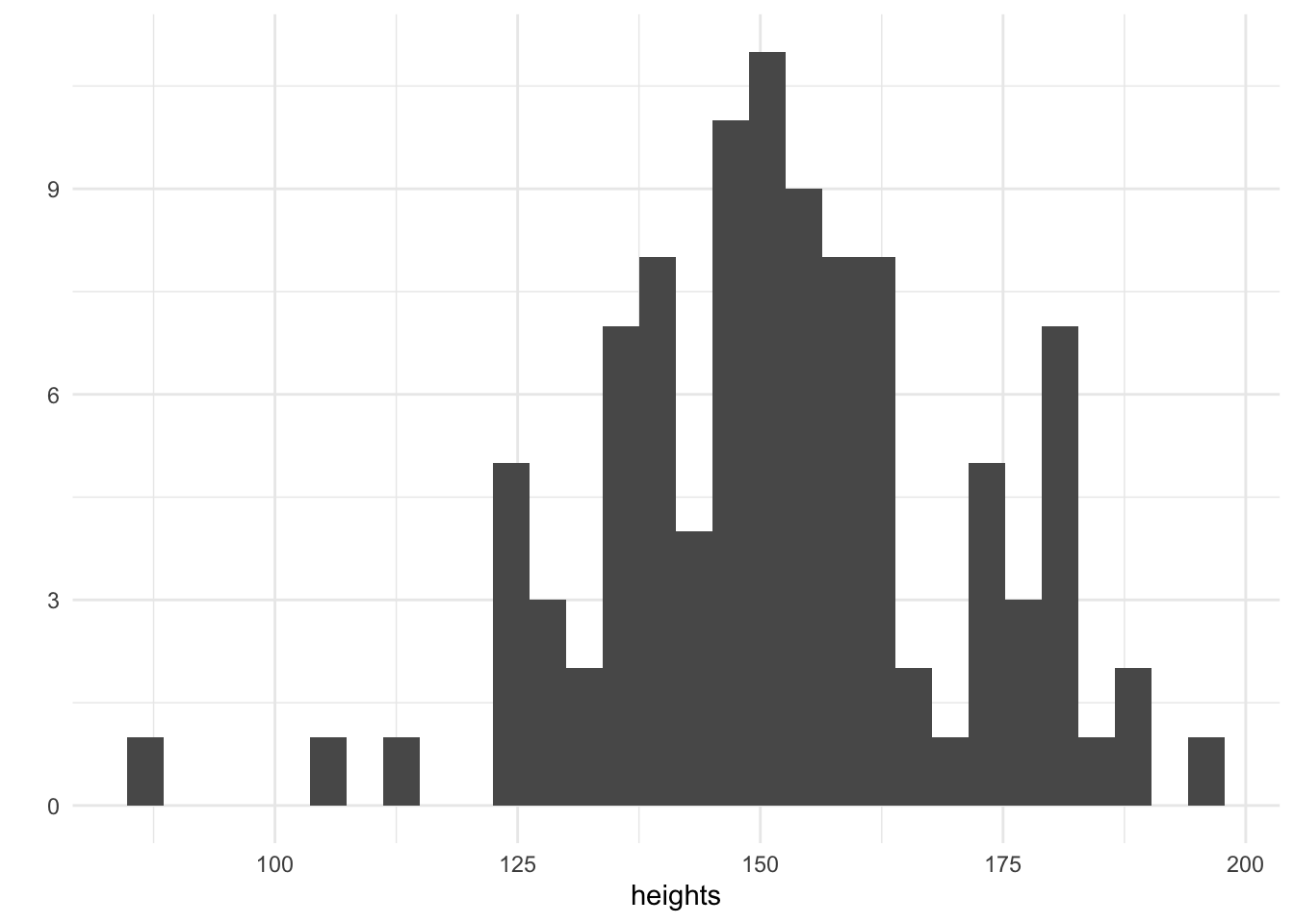

heights <- rnorm(100, mean = 150, sd = 20)

qplot(heights, geom = "histogram")

Jonny Law

June 14, 2019

Linear regression models are commonly used to explain relationships between predictor variables and outcome variables. The data consists of pairs of independent observations

The parameters of the model include the intercept (or overall mean)

In order to manufacture a deeper understand of linear regression it is useful to explore the model as a data generating process. This allows us to understand when linear regression is applicable, how to effectively perform parameter inference and how to assess the model fit. If the model is suitable for the application, then synthetic data from the model with appropriately chosen parameters should be indistinguishable from real observed data. The parameters used to generate the simulated data are known and hence inference algorithms should be able to reliably recover these parameters using the simulated data.

First consider a simple linear regression (a regression where there is only one predictor variable) which links height to weight. We assume that height will be of adults and measured in cm. This is a continuous variable and we might think that this could be modelled using a Normal distribution with a mean of

We have simulated 100 heights and plotted them on a histogram. The tallest adults are 200cm and the smallest are 100cm. Now that we have our heights, it remains to choose a suitable value for the parameter

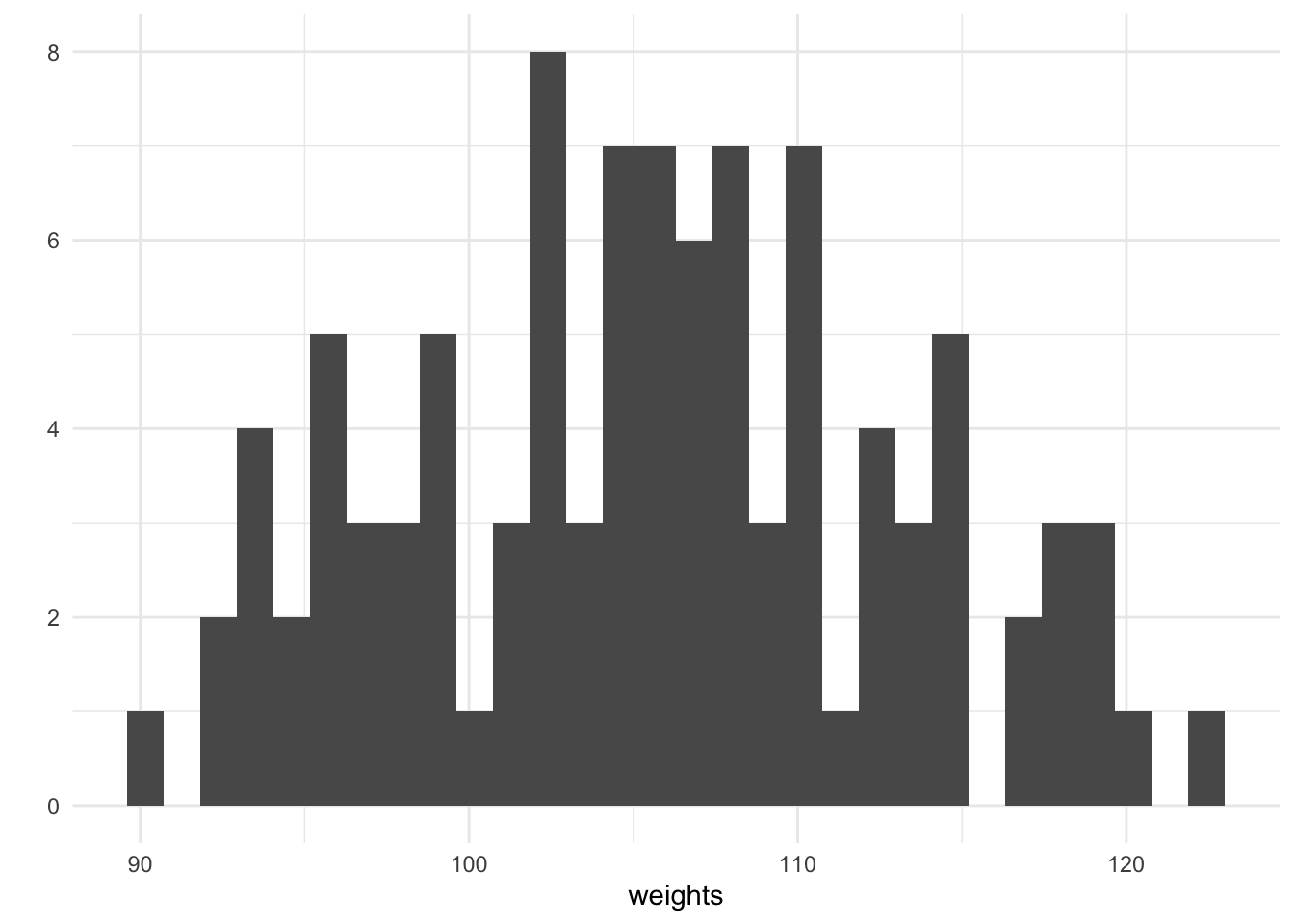

alpha <- 60

beta <- 0.3

sigma <- 5

weights <- purrr::map_dbl(heights, ~ rnorm(1, mean = alpha + beta * ., sd = sigma))

qplot(weights, geom = "histogram")

For every height, we have simulated an associated weight using purrrs map_dbl. We can plot the height against the weight and see that there is a generally increasing trend, this is expected since our chosen value of the coefficient

When performing an applied analysis in a business context, it might be tempting to stop here after plotting the relationship between height and weight. However these heights and weights are only a sample of a population - we wish to make statements which pertain to the entire population. If we consider the sample representative of the population then a properly fitted statistical model will allow us to make statements about the population which this sample is drawn from. As an example of a common business problem, this could include sales of a product - we wish to make statements about future sales which we can’t possibly have seen and hence a statistical model is important.

A parametric model is described by a distribution

In the Bayesian paradigm, the parameters also have a distribution. Before the data is observed, this is referred to as the prior distribution

The likelihood for linear regression with

note that the likelihood is parameterised in terms of the precision

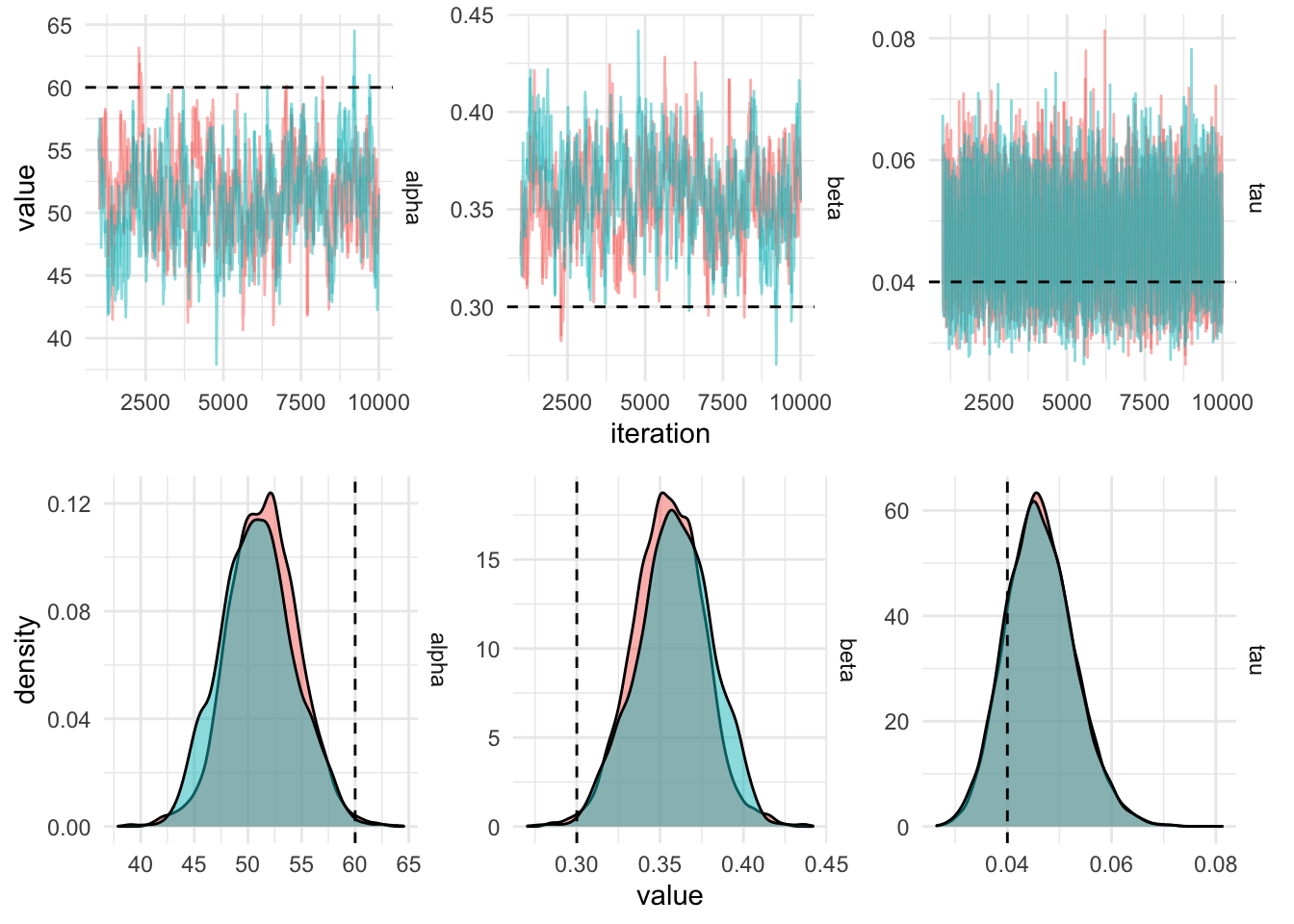

Gibbs sampling works by alternately sampling from the conditional conjugate distribution. It can often be faster for models which are specified using the conjugate structure, however the choice of prior distribution is not flexible (but the parameterisation is). The algebra below is not required to implement a Gibbs sampling algorithm as there are probabilistic programming languages such as BUGS and JAGS which work out the required maths.

Using the likelihood and priors from the section above we can derive the conditionally conjugate posterior distributions:

$$

$$

This allows us to construct a Gibbs Sampler for the linear regression model by alternating sampling from the precision, R as:

sample_tau <- function(ys, alpha, beta, alpha0, beta0) {

rgamma(1,

shape = alpha0 + nrow(ys) / 2,

rate = beta0 + 0.5 * sum((ys$y - (alpha + as.matrix(ys$x) %*% beta))^2)

)

}

sample_alpha <- function(ys, beta, tau, mu0, tau0) {

prec <- tau0 + tau * nrow(ys)

mean <- (tau0 + tau * sum(ys$y - as.matrix(ys$x) %*% beta)) / prec

rnorm(1, mean = mean, sd = 1 / sqrt(prec))

}

sample_beta <- function(ys, alpha, tau, mu0, tau0) {

prec <- tau0 + tau * sum(ys$x * ys$x)

mean <- (tau0 + tau * sum((ys$y - alpha) * ys$x)) / prec

rnorm(1, mean = mean, sd = 1 / sqrt(prec))

}Then a function which loops through each conditional distribution in turn is defined using the three functions defined above. Each conditional distribution is dependent on the parameter draw made immediately above.

gibbs_sample <- function(ys,

tau0,

alpha0,

beta0,

m,

alpha_tau,

beta_tau,

mu_alpha,

tau_alpha,

mu_beta,

tau_beta) {

tau <- numeric(m)

alpha <- numeric(m)

beta <- numeric(m)

tau[1] <- tau0

alpha[1] <- alpha0

beta[1] <- beta0

for (i in 2:m) {

tau[i] <-

sample_tau(ys, alpha[i - 1], beta[i - 1], alpha_tau, beta_tau)

alpha[i] <-

sample_alpha(ys, beta[i - 1], tau[i], mu_alpha, tau_alpha)

beta[i] <- sample_beta(ys, alpha[i], tau[i], mu_beta, tau_beta)

}

tibble(iteration = seq_len(m),

tau,

alpha,

beta)

}

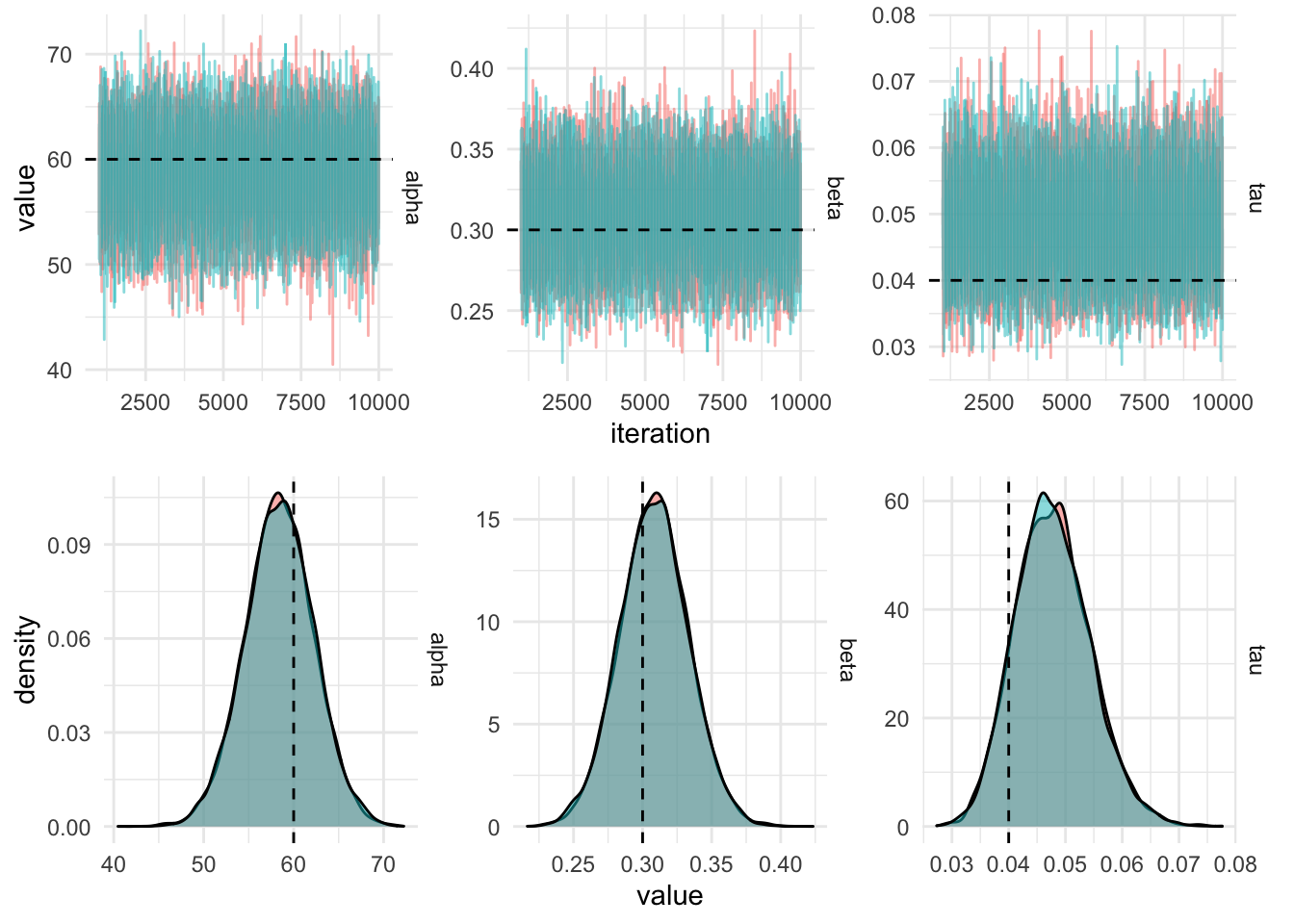

In order to get this chain to mix better, the predictor (the height,

gibbs_sample_centered <- function(ys,

tau0,

alpha0,

beta0,

m,

alpha_tau,

beta_tau,

mu_alpha,

tau_alpha,

mu_beta,

tau_beta) {

tau <- numeric(m)

alpha <- numeric(m)

beta <- numeric(m)

tau[1] <- tau0

alpha[1] <- alpha0

beta[1] <- beta0

mean_x = mean(ys$x)

ys$x = ys$x - mean_x

for (i in 2:m) {

tau[i] <- sample_tau(ys, alpha[i - 1], beta[i - 1], alpha_tau, beta_tau)

alpha[i] <- sample_alpha(ys, beta[i - 1], tau[i], mu_alpha, tau_alpha)

beta[i] <- sample_beta(ys, alpha[i], tau[i], mu_beta, tau_beta)

}

tibble(

iteration = seq_len(m),

tau,

alpha = alpha - mean_x * beta,

beta

)

}iters_centered %>%

filter(iteration > 1000) %>%

gather(key = "parameter", value, -chain, -iteration) %>%

plot_diagnostics_sim(actual_values)

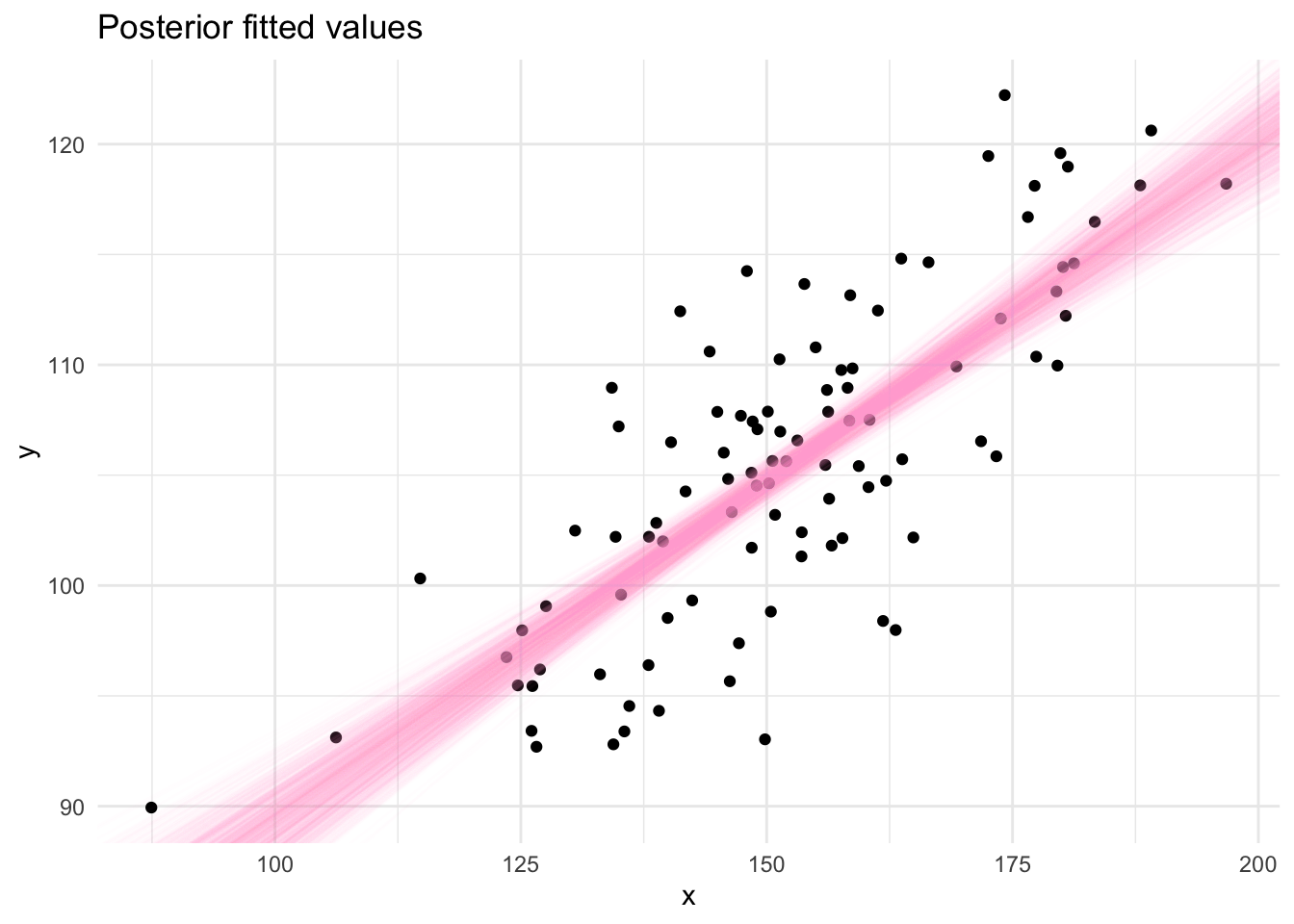

The draws from the Gibbs sampling algorithm are draws from the posterior distribution which can be used to produce summaries required for inference using the linear model. Posterior fitted values, ie. a straight line, can be plotted by sampling pairs of values (

@online{law2019,

author = {Law, Jonny},

title = {Bayesian {Linear} {Regression} with {Gibbs} {Sampling} in

{R}},

date = {2019-06-14},

langid = {en}

}